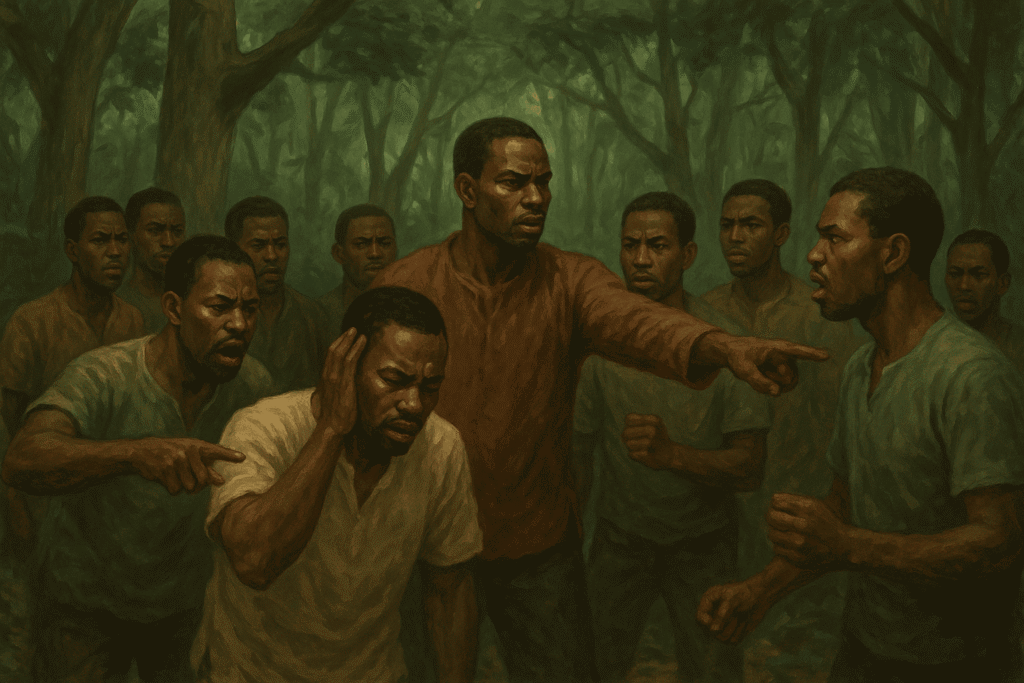

At the center of a stubborn, uncharted forest, a dozen Ghanaians lost their bearings. They had ventured in to seek new horizons, but the trees closed in like walls. Evening after evening, shadows lengthened, fatigue set in, and one truth became undeniable: they had no plan, no map, and no shared way forward. Their ordeal echoed a larger story—of a country rich with promise, yet slowed by faction and the absence of a common blueprint.

The First Voices

Kwame, bold and persuasive, stepped up first. “Trust me,” he urged. Strength and certainty were his tools. The group, too tired to contest, fell in line. Days bled into weeks. Paths curved back on themselves. Confidence alone, they learned, doesn’t straighten a crooked trail. Frustration boiled up. Kofi, fierce and restless, seized command next. He veered left, right, then left again. New direction, same result: more circles, more doubt.

Years of Drift

Names rotated like seasons—Yaw, Ebo, Mensah—each offering a fresh theory, each unraveling under the forest’s quiet indifference. Arguments multiplied. Blame became a ritual. The wilderness did not care whose turn it was to speak.

A Different Proposal

Four years on, the men reached a river and finally stopped. In the hush that followed, Hene Aku—quiet, careful—broke the pattern. “We’re solving the wrong problem,” he said. “We keep searching for the one right leader. None of us knows the whole route. What if we assemble what each of us knows and build a map together?”

Drawing the Map

They hesitated. Cooperation sounded fragile after so much rivalry. But exhaustion can make room for new thinking. One by one, they shared fragments: a bend in the river, a ridge of rocks, a stand of twisted baobab. The first attempts were messy. Disagreements flared. They corrected, revised, and argued again. Slowly, the fragments aligned. The sketch became a map.

Learning to Trust

As their map took shape, something sturdier than enthusiasm appeared: trust. No single mind contained the path, yet the group did. The map became their standard—not a slogan, not a personality, but a shared reference that outlasted moods and egos.

Out of the Trees

With the map in hand, they moved differently. At each fork, they checked the drawing, debated, updated, then advanced. Disagreements persisted, but decisions were anchored to a common guide. The forest, once a maze, began to yield patterns. Months later, they broke into open ground and saw the faint glow of a village. Relief came first, then a quiet pride: they had escaped not by choosing the loudest voice, but by aligning around a standard they built together.

What the Map Means

Hene Aku studied the worn sheet. “This saved us,” he said—not a single idea, but a lattice of many. The others nodded. They had traded rivalry for a framework, and the framework had carried them through.

A Vision for Ghana

Ghana’s story can follow the same logic. Our nation is abundant in talent, culture, and resources; scarcity is not our defining constraint. The friction lies in how we choose direction. We swap leaders and slogans, and the terrain remains unmoved. Progress requires a map: a set of shared standards that outlive political cycles and personalities.

The Shared Standards We Need

- Common Data and Open Goals: Agree on measurable national targets—education outcomes, health access, energy reliability, job creation—and publish the numbers regularly.

- Stable Rules: Lock in predictable regulations for land, taxation, and business formation so planning spans decades, not months.

- Local Problem-Solving: Empower districts with clear mandates and budgets, and compare performance transparently.

- Maintenance First: Fund the upkeep of roads, water, power, and digital networks as rigorously as new projects.

- Talent Compacts: Align schools, training centers, and industry around skills Ghana needs now and next.

- Accountability by Design: Tie funding to results and make course-corrections routine, not scandalous.

From Personality to Practice

Leadership still matters, but as stewardship of a map, not a detour from it. When arguments arise—as they will—the map should settle them. When new facts appear—as they must—the map must be revised. This is how a nation moves steadily, even when voices differ.

Stepping Into the Clearing

The twelve travelers did not change the forest. They changed how they moved through it. Ghana can do the same—by trading improvisation for institutions, impulses for standards, and rivalry for shared work. The light beyond the trees is not a miracle. It is the predictable result of people who choose a common map and keep walking.